Church After Christendom

What role does authentic community serve in proclaiming the gospel?

The death of Christendom has been a revealing time for evangelical churches throughout the West. Stripped of their place of social privilege and prominence, many find themselves ill-equipped to address the relativism, indifference and religious marginalization that increasingly characterize the post-Christian world of today.

Some church leaders are convinced that they will be able to ride out the storm if they just “keep being faithful.” Others think it will be enough to follow the latest preaching or programmatic fad.

However, if Western churches are to effectively and faithfully engage the post-Christian world and serve as beacons of hope, it will not be enough to put a new façade on a deeply flawed structure. Instead, they must reclaim a truly biblical, missional ecclesiology. They must become what British authors Tim Chester and Steve Timmis have called gospel-centered churches.1

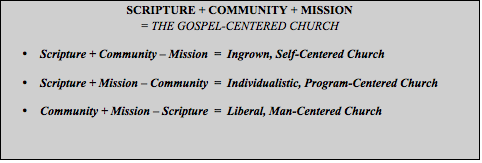

For this to happen, Western churches must place a renewed emphasis on biblical authority, authentic community and missional identity. This diagram illustrates the importance of each element:

Let me focus on what I mean by authentic community. (You can explore the rest of my thinking on this topic—further fleshing out that formula—at the Journal of Urban Mission.)

No one is an island

One of the key characteristics of the post-Christendom age is an “idolatrous notion of self-sufficiency,” writes James K. A. Smith, in Who’s Afraid of Postmodernism? If the church is to effectively minister, it must lay aside these syncretistic, idolatrous trappings of Western individualism and place a renewed emphasis on authentic Christian community.

The seductive worldview of self-sufficiency has had a dramatic influence on the entire Western church, but its influence has been perhaps most noticeable in the evangelical community. That’s due to evangelicalism’s emphasis on God’s saving purpose for the individual. With the rise of modernism and then postmodernism, this emphasis on personal faith was slowly co-opted by an individualistic faith that often had more to do with Western cultural values than with the Christian gospel.

Community has always been an essential part of the Christian faith. The evidence is overwhelming: God created man and woman to live in community. He called Israel into existence as a community of hope and salvation. The very first Christians were gathered into communities called churches. The early church understood itself as constituting a new family. Christian spirituality and discipleship, far from being individualistic endeavors, have always been rooted in the community-oriented “one anothers.” Effective Christian witness is bound up in the community’s love for its members (John 13:35).

Even the vast majority of the New Testament books and their commands are written to and can only be genuinely fulfilled by communities of believers. “The gospel is not a purely personal matter,” writes Robert Banks in Paul’s Idea of Community. “It has a social dimension. It is a communal affair.”

Made for each other

Both studies and personal experience make clear that many Westerners simply do not care about the message of the Christian gospel. Consequently, they often express little willingness to discuss it. But this is precisely why the issue of community is so important: The church itself is a glimpse of the Kingdom of God; it’s where the transforming power of the gospel is most clearly seen and experienced. Consequently, the verbal gospel may be rejected as irrelevant, but its visible testimony in the church will not be so easily ignored.

When lived before a watching world, authentic community is deeply attractive. Individualism may appeal to humanity’s desire for autonomy, but it cannot cover up the fact that men and women were made for community. Speaking from their church-planting experience in England, Tim Chester and Steve Timmis write in The Gospel-Centred Church:

“Time after time people have been attracted to the Christian community before they were attracted to the Christian message. Of course, attraction to the Christian community is not enough. The gospel is a word. Conversion involves believing the truth. But our generation—and perhaps there is nothing special about them in this—understands the gospel message better when it is set in the context of a gospel community.”

Whereas individualism and sin ultimately result in fractured relationships, authentic Christian community demonstrates that there is another way, a way in which men and women, rich and poor, blacks and whites, Basques, Spaniards, Gypsies, Arabs, Asians and Latinos genuinely come together as brothers and sisters under the saving and transforming lordship of Jesus.

It is not enough to say that the gospel can reconcile people with their heavenly Father; churches must show that the gospel can also unify people with their very human neighbors. They must demonstrate that they are capable of accomplishing through Jesus what humanity has never achieved through any government agency, nonprofit organization or military machine.

Looking outward

My attempts to plant house churches and start small groups have made clear that authentic community is much more difficult and demanding than most people imagine. A very genuine desire for community often clashes in practice with an equal or even greater desire to maintain individual autonomy. At other times it clashes with a related desire to protect one’s own privacy, intimacy or even the appearance of spirituality.

Authentic Christian community will always fall apart when joined together with any such human expectations or conditions. The church cannot seek community on its own terms; only on God’s. That will require a biblical, missional love for God and for neighbor, because community can never be an end in and of itself. Otherwise the church becomes “inward-looking rather than missional,” according to Stuart Murray in Church After Christendom.

Authentic Christian community must exist for the sake of mission unto God’s glory, or it will become the enemy of mission to the detriment of God’s glory. There is really very little middle ground.

When gospel mission is not at the core, a community becomes incapable of reaching an unbelieving world, proving itself neither attractive nor provocative, neither inviting nor prophetic. Like the Israel of old, an inward-looking community will begin to view outsiders as a threat to the good thing they have going on instead of viewing them as objects of divine love. If a community does not exist for the good of the world, it is not and cannot be authentically Christian.

The Western world has changed, but the need for the gospel remains. What the church requires is not a new strategy, but a renewed, gospel-centered heart and an expression of authentic community if it is to awaken from its long slumber of complacency.

Tim Chester and Steve Timmis, Total Church: A Radical Reshaping Around Gospel and Community, page 16.

Send a Response

Share your thoughts with the author.