Seismic Shifts: Islam and the World

How now should we preach, teach and write?

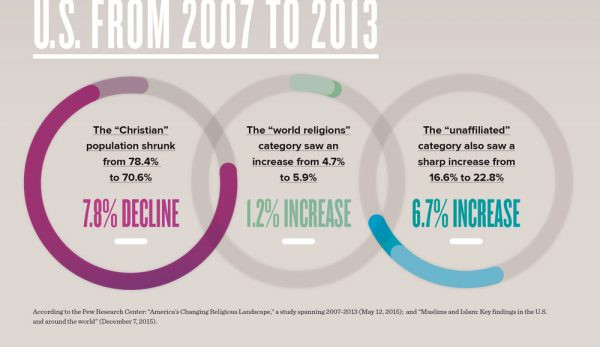

As church leaders, we must pay attention to our world’s changing religious landscape. Without a doubt, we are witnessing an unprecedented shift in populations due to war, natural disasters, economic disasters and political upheavals.1

Therefore, mission-minded believers who are looking for Somalis can go to Somalia, but also now to Minnesota or Maine. Communities of Pakistanis can be found in both London and Chicago, while Iranians are highly visible all across Southern California (Tehrangles).2

The two great evangelistic religions in the world are Christianity and Islam. What sets Islam apart from other world religions is its direct and pointed teaching about Christianity and Judaism. Islamic theology claims to be the original monotheistic religion of Abraham. Thus, it contains shadows of the creator God and biblical characters but denies core Christian truths.

I fear, though, that western Christians are unable to discern the differences and adequately respond to Muslim rhetoric. That’s due to several reasons. For too long, the Christian academy has expounded its disciplines in isolation, not interacting with the broader community and the diverse marketplace of ideas. This isolation, coupled with the current atmosphere of political correctness and an increasing biblical illiteracy, leads to believers unfamiliar with the evangelistic nature of Islam.

In the United States, Muslims currently make up 1 percent of the population (roughly 2.74 million)—a percentage that is expected to increase to 2.1% by 2050. Worldwide, Islam is already the second-largest religion, with 1.6 billion adherents. It is projected to be the fastest-growing religious block by 2050, overtaking Christianity by the end of this century.

What I am proposing is that the Church and the Christian academy address Islam in their teaching and writing, in order to effectively counter Islam’s claims.

Biblical stories in the Qur’an

As stated above, Islam is the only major world religion that folds two other monotheistic religions into its teaching. For example, the story of Abraham, Hagar and Ishmael is reenacted in one of the five pillars of Islamic faith, the Hajj (pilgrimage). Muslims who perform the Hajj must run between the two hills of Safa and Marwa, enacting Hagar’s frantic search for water to quench the thirst of her infant son, Ishmael.

According to the Qur’an, Jibreel (Gabriel) helped Hagar find the well of Zam Zam, and Abraham is said to have made at least four trips from Palestine to present-day Mecca.3 The Bible is silent on any such trips, but such travel would have been arduous (3,000 miles over rugged desert terrain).

Other biblical stories are included in the Qur’an, but the redemptive element is missing. Moses receives ample attention, but the tenth plague—and most important—is omitted. An account of Joseph (Surah 12) is closer to the Bible, but with apocryphal embellishments. Even the birth narrative of Jesus has Mary (Mariam in Qur’an)4 giving birth to Jesus under a date palm tree in isolation.5

It is important for Christian students to be aware of these differences and their significance.

In addition to understanding how Islamic teaching differs on biblical stories, a study of Islam needs to include several specific arguments that Muslims make about the Bible being changed6 as well as denials of the crucifixion7 (although a careful reading of the Qur’an seems to leave the door open to the possibility of His death). Christians must also understand why Muslims reject the Trinity and the Sonship of Christ.8 If Jesus is God, they argue, who was running the universe when He died?

Noting distinctives but avoiding extremes

Overall, in our preaching, our teaching and our writing, we need to convey a better understanding of who God is in Islamic theology, so that when our students become pastors and lay teachers, they will be able to speak truth into the milieu of the new tolerance, which seeks to minimize religious distinctives. As it stands, pastors and parishioners are confused by competing voices. One says, “Allah is a false god” and the other that “Allah and Yahweh are the same.”

On this issue, two extremes are to be avoided:

- presenting the worst of Islam and the best of Christianity.9 This rhetoric creates fear that Islam will take over our society, cultural values and citizenship. Instead of letting Scripture inform the way Christians respond, the church often mixes faith with patriotism. Thus fear and national security dominate our thinking rather than the mission of God that Muslims need the gospel. There is confusion over the government’s role to protect citizens (Romans 13)10 and the Church’s role to respond Christianly (Romans 12).

- stressing Islam and Christian commonalities but avoiding the hard truths of Scripture. This rhetoric presents a Jesus of love, acceptance and peace. The focus seems to be on a friendlier version of Christ rather than a call for repentance and following Him as Lord.

Instead of these extremes, our preaching, teaching and writing should be a gentle voice of love and logic that teaches us how to present Jesus as the way, the truth and the life. A few authors are paving the way in this regard. Typically, books on theology expand upon the great debates of the early church that produced the Creeds or the Reformation, instead of addressing today’s broader religious landscape.

Timothy Tennent of Asbury Theological Seminary has written Theology in the Context of World Christianity. From the context of world religions, he uses Islam to discuss theology (God), Hinduism to discuss bibliology, Far Eastern shame-based cultures to discuss anthropology, et cetera. He does the same in a subsequent text, Christianity at the Religious Roundtable. David Shenk has done the same in Global Gods.

Finally, in Jesus, the Son of God, D. A. Carson goes beyond technical explanations of first-century Jewish community to include Muslims who misunderstand basic doctrines of the church. Carson makes efforts to include Islam in other books as well, such as The Intolerance of Tolerance, in which he addresses a cultural shift from “Is it true?” to “Was anyone offended?”

The world in which we live, teach and preach is seeing seismic shifts in populations and ideas. Our students are entering a world in which living and working alongside people of other faiths is now normative. Islam is the only world religion whose foundational teaching redefines and retells the biblical narrative. Our thinking needs to reflect this new reality, and we must prepare evangelical Christians to be relevant in today’s society.

Send a Response

Share your thoughts with the author.